Here we go. It’s budget time.

Local government officials will be making decisions the next couple months on how much our taxes will go up in 2023. While that may sound a little presumptive and negative, I suspect it is also realistic, knowing the price of everything is going up. That would be more bearable however if homeowners’ property taxes had not already seen significant increases over the past four years.

I feel compelled to…

A) follow up on our rather deep dive into property taxes earlier this year, which delved into the hows and whys of homeowners paying a significantly larger share of Wells County’s total property tax levies; and

B) remind local officials of that trend so they can, at a minimum, be alert to any opportunities to alleviate, stabilize or even change that trend.

A brief review.

It started when homeowners began discovering their 2022 property taxes bills were significantly higher that 2021. An unscientific sampling of about 120 residential properties found an average increase of about 20 percent. These ranged from almost 50 percent, with a few, but not many, experiencing an increase of less than 12 percent. In digging into those “hows and whys,” we discovered two significant things:

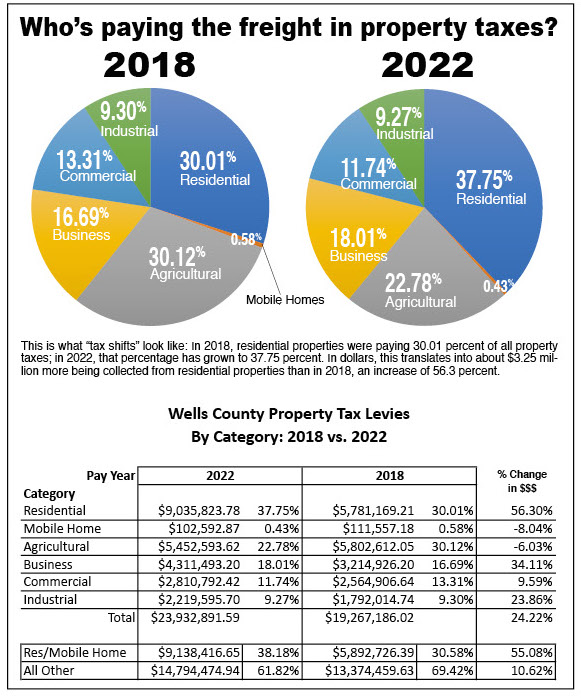

1) Owner-occupied residential property assessments have generally seen significant increases while other categories — business, commercial and industrial — experienced minor increases and often decreases. Perhaps most significantly, agricultural assessments have universally decreased. This all resulted in residential properties paying a significantly higher percentage of the total tax levy. As displayed in the nearby pie chart, in 2018, residential properties paid 30.58 percent of the total bill but that grew to 38.18 percent in 2022. In dollars that translates to about $5.9 million in 2018 to $9.1 million in 2022.

Additionally, because residential property assessments are driven by sales within specific neighborhoods, those increases were quite uneven. While many homeowners have seen their annual bill double and even triple over that four-year period, others have seen very modest increases.

2) On top of those systemic factors that have placed more of the burden on homeowners, Wells County Council made a decision in September 2021 to fund nearly half-a million dollars in jail improvements by reducing the property tax credits, thus placing that new burden totally on homeowners.

What’s new?

Since our last installment in April, taxpayers in all categories have received their new “Form 11: Notice of Assessment of Land and Structures.”

Our home went up a very modest 1.1 percent which was quite a relief after seeing about a 30-percent increase over the past four years. Others were not so lucky.

Dick Johnloz, who lives just north of Bluffton, dropped off his records. His assessment this year went up another 24.5 percent, which makes his past three years’ increase at more than 40 percent. He also notes that for the 14 years prior, he had a total increase of just 1.4 percent.

I revisited 112 of my sampled properties from the spring study and found some neighborhoods with as little as less than 1 percent and other neighborhoods in the 25-to-30-percent range. Individual properties were as high as 57 percent but that could easily be due to some improvements. And there were a couple newer homes that actually saw a decrease, albeit minute — less than one-quarter of one percent. Nonetheless, it seemed a puzzle. How can anyone’s assessed value decrease in this market?

That particular neighborhood on Bluffton’s north side is a bit of an anomaly, Laura Roberts of the county assessor’s office said. While there had been five sales in that neighborhood in 2019, the volume and prices “were slightly lower” in the past two years, thus impacting the 2022 assessment. Which, in my mind at least, further demonstrates the process’ confusing complications. But I digress.

Overall, the 122 properties averaged out to a 10.8 percent increase. That’s still pretty healthy.

Meanwhile, a sampling of 20 business/commercial/industrial properties found a modest 2.15 percent increase.

Farmland assessments, as noted in our earlier series, is a different monster, although I’ve since gone to the Larry DeBoer School of Agricultural Assessments. DeBoer, Purdue University’s agricultural economist, can sum it all up in 14 paragraphs and 691 words. If you’re interested, I can send that to you. A brief synopsis:

Farmland assessed values are based on a statewide base rate per acre, times a soil productivity factor, and for some acreage, minus an influence factor for characteristics such as frequent flooding. That base rate went up significantly from 2008 to 2015, peaking at $2,050 per acre and then fell when commodity prices fell. The rate for 2022 is $1,290 and increased to $1,500 for pay-2023 as commodity prices and farmland sales increase. Those years of significant decreases were part of the cause for homeowners’ share of the pie going up.

DeBoer’s figures match up with my sampling of 27 farmland parcels (three per township) which show a very consistent 16.4 percent increase in valuations.

What’s next?

Local government units — from township trustees, the library board and town councils to Bluffton’s Common Council to county departments, the commissioners and council — will be formulating their 2023 budgets in the next several weeks. What can they do to “alleviate, stabilize or even change” the four-year-trend of homeowners paying a larger slice of the property tax pie?

Well folks, there is not a lot of encouraging news in this regard. In fact, Larry DeBoer shared a presentation he was part of that was made to the Association of Indiana Counties earlier this year in which he predicts that in the next four years, residential property tax liabilities will increase an average of 6.9 percent per year. Agricultural properties will average 6.6 percent while commercial (1.5 percent) and industrial (2.2 percent) will see smaller increases.

“Local officials are pretty much penned in by the state assessment and tax control rules,” DeBoer told me, which makes it difficult for them to have much impact on “property tax shares,” — the percentage of the total each category gets saddled with.

“They could increase the local income tax and assign the relief to homestead (credits),” he added. “That means higher taxes for income taxpayers, though.” He went on to explain the Indiana Supreme Court has set the state’s “assessment standard as ‘objective measures of property wealth.’ For homes, that’s the selling prices.

“In the end, the property tax is a tax on the value of the property, and if your property value goes up faster than others’, you’ll pay more,” he concluded.

What Larry did not suggest, but I will, is that budget decisions be carefully reviewed, with the “wants” separated from the “needs.” And that in any decisions about where new money might come from, a careful review will be made about which category of taxpayers will feel the pain.

Homeowners have felt enough of that.

miller@news-banner.com